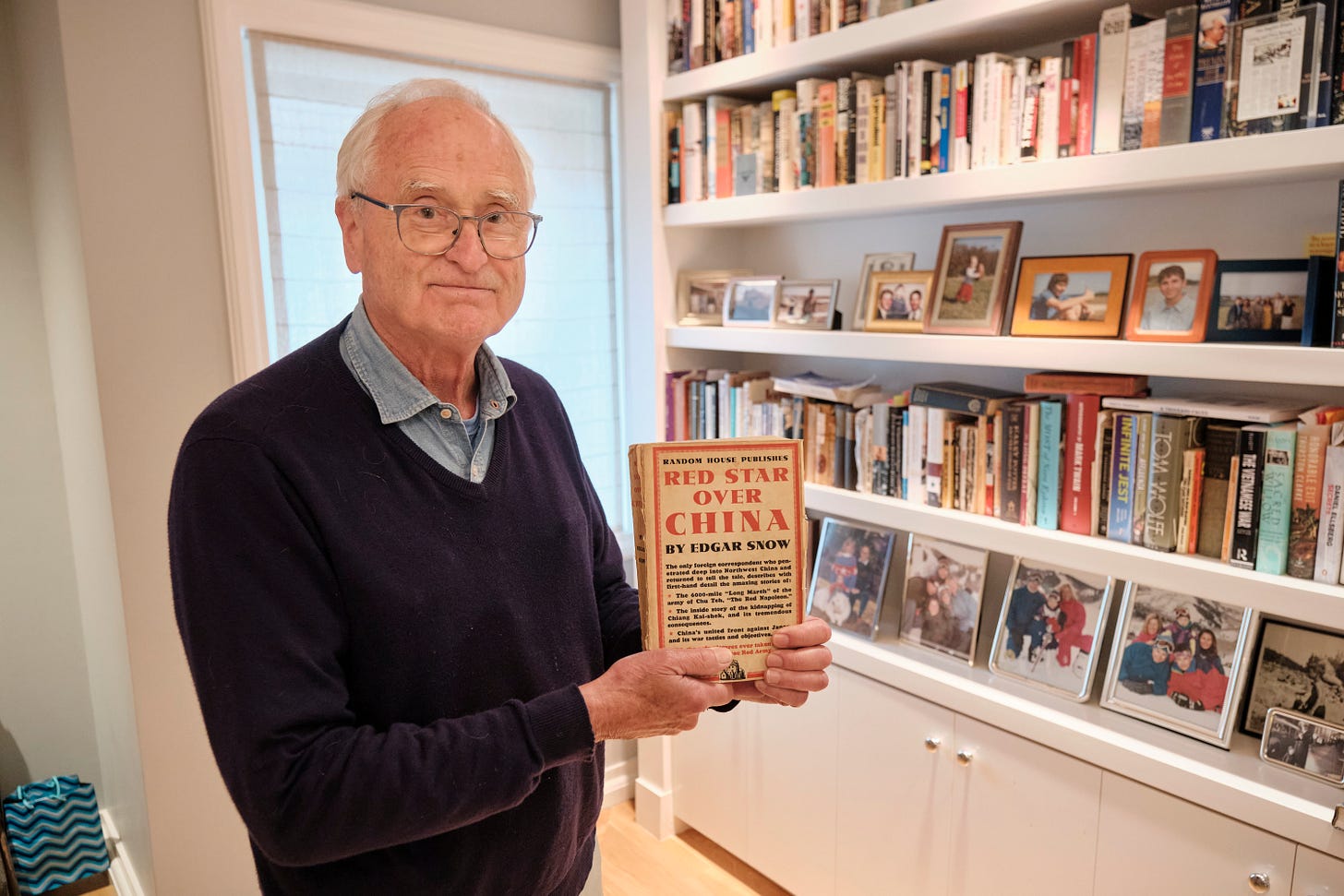

It was fun seeing Fox Butterfield, the first New York Times correspondent in China since 1949, in Portland, Oregon back in July. I last visited Portland in 2022, and you never quite get over the sight of Mount Hood dominating the horizon on a clear summer day in its awesome fashion.

Fox welcomed me to his home, perched on a small hill in a modestly upscale suburb. A history enthusiast, he has lived through and witnessed some of the most pivotal moments in modern history: from meeting Harry Truman as a teenager with his grandfather, to studying under John Fairbank, the progenitor of Chinese studies in America, to reporting on the Vietnam War and helping expose the Pentagon Papers, which earned him a Pulitzer Prize.

Though trained as a China specialist, he only began his reporting inside China in the late '70s, culminating in his book China: Alive in the Bitter Sea. This bestseller set a benchmark for generations of China correspondents. Later in his career, Fox shifted his focus to domestic issues of race and crime, writing acclaimed works like All God’s Children and In My Father’s House.

Talking to Fox was a breeze. I was pleasantly surprised that his spoken Chinese remains impressively sharp — his tones and pronunciations are still spot-on. Of course, we did most of our chatting in English. This piece will explore his early experiences, particularly his family background, his time at Harvard, and his reporting during the Vietnam War. While the bulk of the piece may not focus directly on China, it offers a glimpse into the intellectual formation of one of America's most prominent China watchers and how both domestic and global forces shape U.S. perceptions of China.

Enjoy!

Leo

Index

Seeing China with Joe Biden and John McCain in the 70s

Cyrus Eaton, Lenin Prize and family legacy in Cold War

“Rice Paddies”, and studying under John Fairbank at Harvard

From Pentagon Papers to Vietnam

Reporting on the frontlines in Vietnam

Seeing China with Joe Biden and John McCain in the 70s

Could you talk about your first trip to China?

I was the Hong Kong correspondent for The New York Times from 1975 to 1979 because that’s where we covered China in those days. I couldn’t go to China until 1978, when I attended the Canton Trade Fair. That was my first trip to China; I can barely remember it.

My second trip to China was much more memorable. In 1979, when the U.S. and China were about to normalize relations, China invited the Senate Foreign Relations Committee to visit, and I was invited as a New York Times correspondent. In those days, China had a shortage of hotel rooms, at least for foreigners, so they made everybody room with somebody else. The Chinese government assigned me to room with the naval liaison to the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, who was a Navy captain named John McCain.

For two weeks, John McCain and I were roommates. We had breakfast, lunch, and dinner together and traveled everywhere. McCain's best friend on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee was Joe Biden. So, the three of us did almost everything together for two weeks. That one is easy to remember.

What was your impression of Joe Biden?

Joe Biden was a nice man, very earnest, but he was a typical career politician that when he approached somebody, he always grabbed them by the hand. He was tall, had a strong handshake, and would give them a big smile and grab their hands. He kept doing this to the Chinese, who didn't really know what was going on because they're not used to being touched that way, especially not somebody almost breaking their hand.

So I finally said to him, “Senator.” And he'd say, “No, call me Joe.” I said, “Okay, Joe, please don't grab Chinese by the hand. It's kind of rude and offensive to them, and they don't understand it.” He would say, “Well, why not?” And I said, “Because that's not their custom.” He'd say, “Okay, thank you very much.” And then, five minutes later, he'd do the same thing over and over again.

John McCain and I became good friends, especially because I had seen McCain in prison in Hanoi when I first started working for The New York Times, and we bonded over that shared history during our trip to China. They allowed me to go into his prison in 1969, and I was the first reporter to find out that John McCain was still alive when his jet fighter was shot down over Hanoi.

I saw him then and as roommates 10 years later in China. We had a great time, and I would take him out and say, “Let's sneak away from our handlers and see how Chinese really live and what they really say.” We just went out and talked to people, and he thought this was a lot of fun.

“He said something straightforward and obvious, but I had never thought about it. He said China is the oldest country in the world with by far the largest population. It's a big, important place.”

That’s a wonderful tale. What made you initially interested in China?

When I was a sophomore at Harvard as an undergraduate in 1958, there was a fear that the United States was going to have to go to war with China over those two little islands, which Americans call ‘Quemoy’ and ‘Matsu’ and Chinese people call ‘Jinmen’ and ‘Mazu’.

America's leading sinologist and Harvard professor of Chinese studies, John Fairbank, decided to give a public lecture about the danger of the United States going to war for those two little islands.

I attended his lecture. He said something straightforward and obvious, but I had never thought about it. He said China is the oldest country in the world with by far the largest population. It's a big, important place. Why would the United States want to go to war with China over those two little islands? It made no sense logically. And we had just finished the war in Korea. As I listened to him, I realized, “Gee, I don't know anything about that place.”

So I began to audit his introductory class on the history of East Asia. And in the spring, I decided to take a second class in Chinese history that Fairbank was teaching. As a Harvard undergraduate, I would find out my exam grades at the end of year from a postcard you put in the exam booklet. When I received my postcard back from the final exam, it said: “please come to see me in my office, tomorrow morning at 10.” “Oh no,” I thought I really screwed up my exam.

So I went to see John Fairbank. I was nervous, especially because he was a great man, a big figure on campus, and the Dean of Chinese studies in the United States. So I went in, and he said, “Fox, you wrote a wonderful exam. Have you considered majoring in Chinese history?” I went, “oh, no, I had not considered it.” I was so relieved that I had written a good exam.

He said, “Well, if you are, you must immediately begin studying Chinese.” At that time, Harvard did not teach spoken Chinese, only classical written Chinese, and there were just about 10 people, all graduate students.

So Fairbank said, “here's what you do. Going down to Yale, they have a special program that teaches spoken Chinese in the summer because they have a contract with the Air Force to teach 18-year-old Air Force recruits how to speak Chinese so they can listen to and monitor Chinese air force traffic.”

So I spent the summer at Yale studying Chinese with air force recruits. I took classical written Chinese classes when I returned to Harvard that fall. Luckily, I got a Fulbright Fellowship to go to Taiwan after I graduated, so I studied in the best spoken Chinese program at the time run by Cornell University.

Cyrus Eaton, Lenin Prize and family legacy in Cold War

I wonder whether there's any family influence on your China journey. Your father was the historian and editor-in-chief of the Adams Papers, and your maternal grandfather, Cyrus Eaton, was one of the most prominent financiers and philanthropists in the Midwest. Could you speak on the impact of family legacy on your China journey?

My father certainly instilled a love of history in me. That was always my favourite subject in school and the one I did best in. Eventually, my major at Harvard was Chinese history. My father didn't know anything about China and never went. My mother visited Taiwan and stayed with me for ten days in the 60s.

My maternal grandfather, Cyrus Eaton, would fit the Chinese notion of a rags-to-riches success story. He grew up in a small fishing village in Nova Scotia, Canada, and went to college in Toronto with the help of an older cousin. This cousin went on to become a Baptist minister in Cleveland, Ohio, across the lake. Among the people in his parish was a man named John D. Rockefeller — yes, the original John D. Rockefeller.

The cousin invited my grandfather and said he had a job for him. So my grandfather started off as a golf caddy for John D. Rockefeller and then a messenger. Ultimately, he founded his own electric power company in Cleveland — Ohio Electric Power — and became quite influential. He had multiple companies but then lost everything in the Great Depression.

During World War II, my grandfather heard about a large iron ore under a lake in Ontario through his Canadian connections. By then, he had already formed connections with President Roosevelt and then Truman, so he said, “If you can give me some money and help underwrite this, I can get Canadian permission to drain the lake for the iron ore deposit,” which became the world’s richest iron ore mine, Steep Rock Iron Ore. That’s how he got back into business. Truman and my grandfather ended up having a close connection, and he used my grandfather's train to campaign for re-election in 1948. My grandfather was an unusual man. He had a real vision about things.

He was trading metals with the Soviet Union as well.

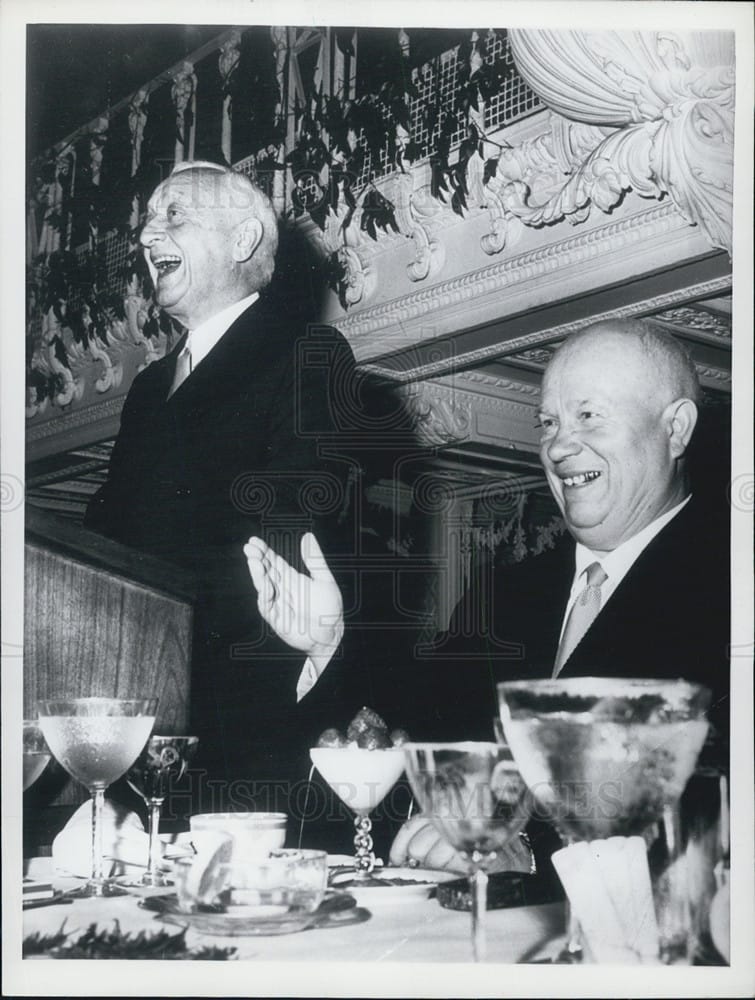

I don't know the details, but when Khrushchev came to power, my grandfather became interested in trying to work out some arrangement between the United States and Russia, which is where the Pugwash movement came from. He was inviting Russian and American scientists to meet. They couldn’t meet in the U.S. because it was against American law, but he arranged for them to meet in his hometown of Pugwash, Nova Scotia. We had American and Russian nuclear physicists meeting to discuss nuclear weapons in this little village. Eventually, he invited some Chinese people to come.

At one of these conferences, I met Harrison Salisbury, an editor of The New York Times and the first NYT Moscow Correspondent. I was just starting out as a stringer for The Washington Post, but Salisbury saw something in me and suggested I send him a story. That connection eventually led to my job at The New York Times.

He must have known people pretty high up in China too.

I don't know the China connections; he didn’t know Mao or Zhou Enlai. He did have a close relationship with Khrushchev, to the extent you could. It started with the Pugwash movement.

He just sent a telegram to Khrushchev and became friends?

Yes. What do you call that, guanxi?

I guess so. Do you remember when he won the Lenin Peace Prize?

I do. I think I was in Taiwan at the time. I didn’t go to the ceremony.

How did you feel about his activities growing up?

I was never too sure what was going on. My mother had the intelligence of her father—in fact, she looked remarkably like him—but she was skeptical because she always felt that he was making all these big deals but wasn't looking out for his own family.

What was your mom like?

My mother was a smart woman. She went to Bryn Mawr during the Depression, but my grandfather refused to let her take a scholarship because it would signal he had no money. She worked full-time while in school and graduated near the top of her class. She was angry at him for making her life difficult for his own pride.

My mother worked all her life. By the time I reached college, she was working at Harvard University, which was unusual for the time. She started as a secretary but eventually became the registrar in charge of all the records. When she died in 1978, the Harvard Crimson published a tribute saying she had been the most helpful person to many undergraduates.

What did you want to become as a teenager?

I wanted to be a baseball player. Yes, for a long time my life revolved around baseball. I thought I was pretty serious. Some time in college, I realized I wasn't going to become a major league baseball player, and I became much more interested in the life of the mind.

“Rice Paddies”, and studying under John Fairbank at Harvard

Did you think of Asia growing up?

There was really almost nothing until I mentioned, in my sophomore year, when I was 19, beginning in 1958 as an undergraduate at Harvard studying with John Fairbank. No courses offered at high school that I could have gone to. Even at Harvard, the Chinese history class was almost all graduate students. Harvard undergraduates could take an introduction class to the history of East Asia, which included China, Japan, and Southeast Asia. Harvard students nicknamed this course “Rice Paddies.”

That's the famous course by Fairbank and Reischauer. What was it like studying with those two legends?

Well, they were both significant people in every way. Fairbank helped start the field of Chinese history in the United States. Reischauer certainly started studying Japanese history.

In my first year, they had just finished a textbook for the Rice Paddies course. It had not been published as a book yet, just a mimeograph form. They gave us these big books you had to carry around, like carrying one of those old store catalogues with hundreds of pages printed on one side. You would bring these things into class. One was called East Asia: The Great Tradition, and the other East Asia: The Modern Transformation.

What was John Fairbank like as a person?

Intimidating. He was a tall, bald man, always looking over his glasses at you. But he was charming and friendly, and if he sensed that you were interested in his field, he would do almost anything for you. He reached out to students in a way that few other faculty members did.

“He was an academic entrepreneur and missionary for Chinese studies, and was creating the field of Chinese history in the United States. Before him, Chinese history didn’t exist for most Americans to study.”

And he had regular gatherings at his house.

Yes. His house was a little yellow wooden house dating back to the 18th century, right in the middle of the campus. Harvard had given it to him, and every Thursday afternoon, anybody interested in China who was in Cambridge that day was invited.

You never knew who you were going to meet. Fairbank was a kind of social secretary. When you walked in, he’d greet you with a handshake and then take you around to introduce you to some people. He did that all the time with people. He was an academic entrepreneur and missionary for Chinese studies and was creating the field of Chinese history in the United States. Before him, Chinese history didn’t exist for most Americans to study.

I always wanted to major in history. That subject appealed to me and was my strongest area of study. I took some American history and intellectual history classes, but the Chinese history class became the one that I really focused on. I couldn't tell you exactly why, but it was interesting to me. The more I read, the more I liked it. After that first Fairbank class, I signed up for the more intensive modern Chinese history class and whatever else Harvard had.

I signed up for a Japanese history class, too. At the end of my senior year, John Kennedy named my professor Edwin Reischauer his ambassador to Tokyo. So, on my way to Taiwan as a Fulbright scholar, I stopped in Tokyo to meet Reischauer at the US Embassy, and two of Reischauer's grown children took me around Tokyo. I reported in Tokyo later in my career.

Was Ezra Vogel working on Japan at the time?

Yes, Ezra had. Ezra was in my Spanish class in the first year. He hadn’t yet decided what he would focus on then. We sat next to each other. We were always personal friends even though he was a bit older. He was a nice man and became a professor later.

I sat in the same classroom with several other older people who went on to teach about China, including Dorothy Borg. Even then, she had white hair. She worked for the Council on Foreign Relations in New York but was taking classes at Harvard. When I first went to China, she was still involved with China.

So, from that group of Americans studying China at Harvard at that time, many went on to do things related to China, including Orville Schell, Andy Nathan and me. I did not know Perry Link while in Harvard.

Many major figures in China studies today were at Harvard with you.

Yale had Mary and Arthur Wright, but they were graduate students at Harvard with me and went on to become full professors at Yale. This must be because that was a place where Fairbank was an evangelical figure that people gravitated towards, and he was preaching this new faith of Chinese studies.

From Pentagon Papers to Vietnam

What did you do after Harvard?

I spent a year in Taiwan when I graduated. I wanted to stay, but Fairbank hurried me up to get back to graduate school.

Did you listen to Fairbank?

I was going to get my PhD at Harvard and teach Chinese history, but after five years, I became less interested in actually studying Chinese history.

During the 1960s, the Vietnam War happened. Vietnam is kind of a cousin of China, so I started reading everything I could about Vietnam. I even started a course on Vietnam so that Harvard undergraduate and graduate students could learn about Vietnam.

I got a fellowship to return to Taiwan to work on my dissertation about Hu Hanmin. At that time, many American GIs were coming to Taiwan on what we call R&R — “rest and recreation.” The U.S. government made a deal with the American military that anyone who served in Vietnam for a year had an automatic R&R, a paid week leave to go anywhere in Southeast Asia. Many chose Taiwan to chase pretty young Chinese girls. So, GIs would show up in Taiwan and didn't know what they were doing. I would see them on the street, go up and talk to them.

I became more interested in Vietnam over time. A friend told me, “You're spending so much time reading newspapers about Vietnam, you should become a journalist.” It hadn't occurred to me. By chance, I met a correspondent from The Washington Post, Stanley Karnow, who was the Hong Kong correspondent for the Post and covered Vietnam for quite a while. He asked me to be his stringer, a part-time assistant. So I would send my story to him, but he'd never do anything with it.

I was discouraged, and that's when I met Harrison Salisbury through my grandfather in Montreal. Salisbury asked me to send stories to The New York Times. I thought I was a traitor to my job with The Washington Post. But it wasn't really a job; it was in my imagination.

When I sent Salisbury my first story, I received a cable from the foreign editor of The New York Times saying they had put my story on the front page and given me a byline. My parents at home in Cambridge, Massachusetts saw it that morning, and they wondered, what is Fox doing?” They thought I was working on my PhD dissertation.

“Oh, that looked like our son there.”

The story was about Chiang Kai-shek's son, Chiang Ching-kuo, who was becoming Chiang Kai-shek's successor. I wrote about how he was going about it. That was a good news story, so The New York Times sent me a message and said, “If you'd like to work for us, we'll be happy to take more stories.”

So I started sending them stories once or twice a week, and after four or five months, they gave me a job offer in New York. That was just one of those lucky breaks. I guess The New York Times correspondent who made that initial contact with me, Harrison Salisbury, who had won several Pulitzer Prizes, must have seen something in me.

What's your relationship with your editors over the years?

Generally pretty good. They certainly intimidated me at the beginning. The person who actually hired me was the foreign editor at The New York Times, James Greenfield.

When I returned to New York, it was New Year's Day, the end of 1971. James asked me about my training and asked me to spend the next couple of months sitting at the foreign desk to watch how they do things. I couldn't even write stories for a while; I just handed them the copy that came up. I later got promoted to news assistant and was asked to find something interesting and write one story a week. I wrote some stories about Asia for the newspaper.

They wouldn't give me a byline at first as I wasn't a reporter. My first assignment was to Newark, New Jersey, which had gone through a series of terrible race riots in the late 1960s. I was going to be the correspondent in Newark.

This was after they hired you and during those two years of training?

Yes. One day, I was covering a story. The new mayor of Newark — the first black mayor of a major American city — called a meeting in city hall to see if he could stop the riots.

He was trying to bring people together: white, black and Hispanic. Within ten seconds, everybody was having a fistfight. People were knocking each other out with the police and mayor in front of them. The mayor yelled at people to stop, and they still kept punching and hitting each other with big pieces of wood right in City Hall.

And I was there. Two very large black men grabbed my arms behind my back. The nasty term for white people in those days was “honky”. They said, “What are you doing here, honky?” They began punching me in the stomach and hitting me in the head. I thought I was going to die right there before I finally broke free. I got to my office to send my story of the city hall by telephone across New York City. And they put that story on the front page.

Your second front page at The New York Times.

So the editor of The New York Times was a very intimidating man, Abe Rosenthal, a gifted correspondent who'd won several Pulitzer Prizes. He won a Pulitzer Prize in Poland and Germany. I got this message saying, “Mr. Rosenthal wants to see you in his office immediately.”

I thought, “oh jeez I'm getting fired.” I just got beaten up in City Hall and they're going to fire me. So I walked in, and he said, “Fox, that was a really nice story.” He said, “you did a really good job on that story. We have another assignment for you. I want you to go over to the New York Hilton Hotel”, which was about ten blocks away.

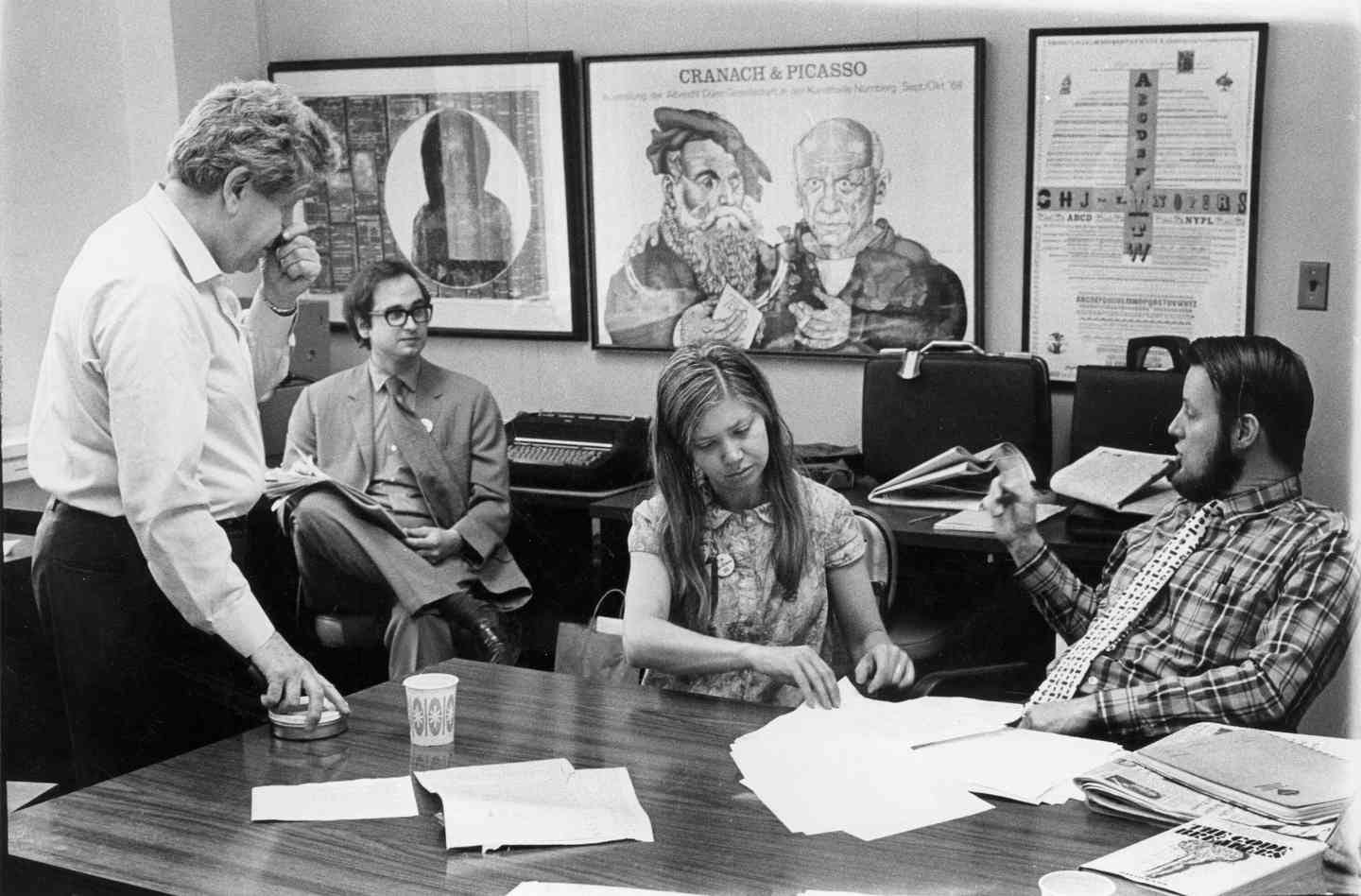

He told me that one of our correspondents, Neil Sheehan, had gotten a secret government document, the Pentagon Papers, which were boxes and boxes of government documents. Neil couldn’t read all that by himself, so I had to go and read it with him. Besides, I knew about Asia.

By that point, I had read as much as I could about Vietnam. I also knew Neil Sheen because I had helped him come to Harvard to give a talk about Vietnam while I was a graduate student. So we actually had a good relationship.

I spent the next two months in Neil's hotel room reading documents, but two of us were not enough, so a third and eventually a fourth correspondent were brought in.

Did you understand the risk you were taking working with the classifieds? You could be arrested.

Right, yes. I had to tell my parents, “I can't tell you anything about what I'm doing.”

When we finally started publishing, I wrote three of the seven installments, which was amazing because I was a junior person. Abe Rosenthal called me back into his office after we finished, and said, “Fox, you did a nice job on this, so we're sending you somewhere. We're sending you to Vietnam.” He said, “I want you to go immediately.” So I went from the Pentagon Papers to Saigon.

That was a surprise. That was not where I wanted to go. In fact, what I really wanted was to go to cover China, but that would have meant Hong Kong. But Vietnam turned out to be fascinating. There was always something happening.

Reporting on the frontlines in Vietnam

Can you talk about your Vietnam experience?

It was an experience at many levels. Intellectually, it was seductive because there was so much going on, people getting shot every day. The only way to truly understand it was to be there.

You could divide the correspondents into those who stayed in Saigon and those who went out to the field. I wanted to be in the field as much as possible. I spent time on Navy ships and even in a fighter plane, hitting what appeared to be factories.

The GIs, or “grunts”, wanted to know what we wrote about them, and some would come to our office in Saigon. Sometimes they were angry. A few correspondents received threats, but we mostly had a good relationship. The more you were willing to go out into the field, the more respect you earned. I was out there from the beginning.

Vietnam was more complicated than I initially thought. If you were strictly anti-war or pro-government, you missed the full picture.

You had been against the war before. How did you feel once you were there?

I was part of the anti-war movement and then found myself in the middle of the war. I got to know many ordinary Vietnamese who were actually happy to have Americans there because the communist soldiers would threaten to confiscate their property. Vietnam was more complicated than I initially thought. If you were strictly anti-war or pro-government, you missed the full picture.

What was the relevance of the Pentagon Papers then?

The Pentagon Papers showed that the U.S. government was deceiving the public, but we were also helping some people. It was more complex than the extreme positions made it seem.

Were you at risk of being arrested for the Pentagon Papers?

Possibly, yes. My name was on the case, but by that time, I was in Vietnam. I put it out of my mind.

How long were you in Vietnam?

I was in Vietnam from 1971 to 1975, with breaks in Japan. The New York Times didn’t let anyone stay more than two years at a time because of the exhaustion of war. But I kept going back and stayed until the last day of the war in 1975 when I left on a helicopter to a Navy ship.

I took the place of a brilliant female correspondent, Gloria Emerson. I inherited her apartment, and Vietnam was as exciting a place as it could be. There was always something to do, something to see, something that you shouldn't see but wanted to see. Vietnam was all that I talked about for four years. I stayed until the last day of the war, April 30th, 1975.

Did you get hurt during the war?

I was hit by mortar fragments and lost my hearing for almost a month. Once, I was left behind after the unit I accompanied ran into an ambush. I had to walk three hours to get back to safety.

Vietnam absorbed all parts of your brain, your mind, your body, and your psyche. It just took over.

How did the war experience change you?

It depends on the individual. Some correspondents loved Vietnam and never wanted to leave. Others were terrified and left without a word. Even today, I still belong to an online Google group of ex-correspondents in Vietnam, and I still get dozens of messages every day. They always want to discuss Vietnam.

Back in the day, some got afraid and just left. I had several friends who would literally just leave a message at their desk saying, “Please pack my belongings and send them back to New York.” It's hard to generalise and have an ironclad rule about. It was different from regular assignments in most other countries.

Well, Vietnam was certainly special.

Vietnam absorbed all parts of your brain, your mind, your body, and your psyche. It just took over. When the war ended, I came out on a helicopter that landed on a Navy ship. The captain said I could make one phone call. I called my editor in New York and said, “I’m out, I’m safe.” He replied, “Good, because we’re sending you to Hong Kong.”

Recommended Readings

Fox Butterfield, 1982, China: Alive in the Bitter Sea

John Fairbank, Edwin Reischauer and Albert Craig, 1965, East Asia: The Modern Transformation, George Allen & Unwin

Edwin Reischauer & John Fairbank, 1958, East Asia: The Great Tradition, Houghton Mifflin

Acknowledgement

This newsletter is edited by Caiwei Chen. The transcription and podcast editing is by Aorui Pi. I thank them for their support!

About us

Peking Hotel is a bilingual online publication that take you down memory lane of recent history in China and narrate China’s reality through the personal tales of China experts. Through biweekly podcasts and newsletters, we present colourful first-person accounts of seasoned China experts. The project grew out of Leo’s research at Hoover Institution where he collects oral history of prominent China watchers in the west.

Lastly…

We also have a Chinese-language Substack. It has been a privilege to speak to these thoughtful individuals and share their stories with you. The stories they share often remind me of what China used to be and what it is capable of becoming. I hope to publish more conversations like this one, so stay tuned!

Correction note: An earlier version of this piece incorrectly referred to sinologists Mary and Henry Wright as "Fords." We thank reader Robert Kapp for bringing this to our attention.

Share this post