When I arrived at Fox’s place, his chocolate lab, Charlie, greeted me with a wagging tail. The rainy weather outside, unfortunately, obscured what otherwise promised to be a stunning view of Mount Hood from Fox’s living room. But the conversation more than made up for what I missed in the landscape. Fox poured me a glass of water and sat opposite me on a grey sofa, wearing a navy blue jumper.

Early this month, we published a piece about Fox’s early study of China under John Fairbank at Harvard and his reporting in Vietnam during the war. The last piece builds up towards this one, which delves into how Fox opened the first Beijing Bureau of The New York Times – the main reason that got me interested in his oral history in the first place.

The press, as a quintessential part of America’s cultural entourage, brought a new window for the American public to understand China. It also symbolised a gesture of goodwill from the Chinese government toward the Western world. On the ground reporting in China was a pivotal step in bridging the two nations and making China’s reality more accessible to the world.

For the keen and curious minds, Mike Chinoy’s Assignment China: An Oral History of American Journalists in the People’s Republic offers compelling accounts from American journalists about their early experiences in the country. Forty years later, this history is only beginning to be told.

Enjoy.

Leo

For quick navigation:

“The New York Times was the People’s Daily of America”

Deng Xiaoping visited the U.S., and a new China dawned

Opening the Times’ first Beijing Bureau in Peking Hotel in the 1980s

Trump, Interactions with other American Politicians and life after China

“The New York Times was the People’s Daily of America”

I studied China as an undergraduate and then graduate student, and lived in Taiwan. However, my first contact with people of the mainland only came in 1972. I was in Vietnam when The New York Times reached out to me. The People's Daily planned to send journalists on a tour of the U.S. before the normalisation of relations. From the Communist perspective, they assumed The New York Times was America’s official publication.

“From the Communist perspective, they assumed The New York Times was America’s official publication. They thought The New York Times was the People's Daily of America.”

They thought you were their counterpart.

Yes, they thought The New York Times was the People's Daily of America. So they asked The Times to help them arrange a tour. I flew back from Saigon to New York and met three men. I still don’t know whether they were really correspondents of the People’s Daily; I’m sure they were ranking members of something. The New York Times provided a car and driver, and we toured The New York Times and saw things in New York City and Washington DC. They especially wanted to see an American corn farm in Illinois, so I arranged it with some agricultural organisations.

A striking thing I remember is the difference between Chinese and American agriculture. The men from People’s Daily were astonished at how tall the corn was. They kept asking, "Where's the irrigation?" The farmer said, "We don’t need it, we have rainfall." That difference in natural conditions struck them. The farm had tractors and trucks, and the Chinese were amazed by how the farmer did all the work by himself.

American farming was already heavily mechanised.

Yes. The next stop was Detroit, where they visited a Ford automobile plant. Again, they were stunned by the level of mechanisation — so few workers, so many machines. The United Auto Workers arranged for the Chinese to stay with three autoworkers’ households. The Chinese didn’t like that; they wanted to be with each other. The autoworker said, ‘No, you can stay with me, and you'll stay with them.’ And so they did; it was almost a political crisis. The Americans were hospitable, but the food was completely different from what the guests were used to. That trip was so revealing to me. They were some of the first officials from the mainland to stay in American households.

I'm sure it was revealing to them, too. This was almost like one of those Chinese friendship trips in reverse.

It was. The Chinese were given all this friendship, but they weren’t quite prepared for what it meant.

Did you ever stay in touch with any of them?

For a while, but they didn't really want to stay in touch with me. The Cultural Revolution was still going on; people had to be careful.

This was 1972, right before Nixon’s visit.

All these things were happening at once. Many little steps led to the big step, and this was a small step along the way.

Deng Xiaoping visited the U.S., and a new China dawned

Another memorable trip was in 1979 when Deng Xiaoping came to the U.S. The New York Times asked me to join the trip, but I was in Hong Kong then. Deng Xiaoping’s trip was in January and February of 1979. We started in Washington, met Jimmy Carter, and went to Atlanta, which was a little strange. I guess they wanted to see the American South. There, Deng signed the first commercial agreement with Coca-Cola to start manufacturing in China.

“The cheerleaders kept coming over to hold the hands of the Chinese delegates. The Chinese didn’t know how to react, ‘Please don’t grab me.’ It was an interesting cultural misunderstanding.”

I’m sure Coca-Cola was very happy that day.

They were. Then, the delegation went to Houston to visit the Johnson Space Center, where American space efforts were concentrated, and attended a Texas Rodeo. The food there was classic American—baked beans, beef, and coleslaw.

The American host kept asking the Chinese to eat the beef. The Chinese didn't know what to do with these enormous pieces of meat. I said that the Chinese are used to having their meat cut up in small pieces; they can't deal with these chunks. The Chinese kept saying it was barbaric to have such large pieces of beef. ‘Niurou (beef) shouldn't be so big.’

One of the most interesting scenes was at a Houston football event where they had cheerleaders — tall American women with blonde hair, short skirts, high boots, and boobs sticking out. The cheerleaders kept coming over to hold the hands of the Chinese delegates. The Chinese didn’t know how to react, “Please don’t grab me”. It was an interesting cultural misunderstanding.

And you were there.

I was there, and I wrote a story in The New York Times. The trip reflected the enormous gap between China and the United States, which the communists had not prepared the Chinese for.

“I remember how excited the Chinese were to be there, how happy the Americans were to see them, and the enormous cultural gaps between the two countries. There was a lot of goodwill. China was still very closed, but things were about to change.”

Certainly not in front of their boss.

The final stop was Seattle. The Chinese delegation was fascinated by Boeing's enormous manufacturing facilities. Ultimately, they signed a deal to start manufacturing Boeing planes in China. That was a big leap forward for China. And the Boeing people were especially friendly because they wanted the deal with China, starting with selling Boeing 707s.

Did anyone on that trip leave an impression on you?

It’s been 50 years now. I remember how excited the Chinese were to be there, how happy the Americans were to see them, and the enormous cultural gaps between the two countries. There was a lot of goodwill. China was still very closed, but things were about to change.

What did you think of Deng Xiaoping at the time?

I met him a couple of times. He was short with a funny accent. Compared to other party leaders, he seemed quite moderate. He’d been through a lot — purged three times in his career, and during the Cultural Revolution, his son fell from a window, severely injuring his lower spine. Deng seemed to realise there were better ways of doing things, though he wouldn’t install an American-style political system.

Did you meet other high officials, like Zhao Ziyang or Hu Yaobang?

I met Zhao in 1980 when I visited Sichuan to see the industrial and agricultural reforms he introduced, which gave factories and peasants more autonomy on what to produce. Zhao agreed to an interview and came to the hotel where I was staying. He arrived by himself, without guards or handlers, which was stunning and unusual. I wrote about this encounter on Page 300 of my book. As the party leader in Sichuan, he attempted some really forward-looking reforms.

Significant things were happening at the time: economic reforms, the Democracy Wall, and even local elections.

I did sense a new China emerging, though being there, many still feared that the Cultural Revolution would go on; at least, they weren’t so sure it was gone. People still did get arrested. But the door was opening, and a little light was coming in.

I had always wondered, given the economic changes, if political changes would go as far. Is there going to be a liberalisation? I was never sure that would happen.

How did you feel when China attacked Vietnam, given your experience with the Vietnam War?

It was a surprise to me and the Vietnamese. It was bizarre. The Vietnamese descended from Chinese people; the name Vietnam comes from Yue Nan, though the languages are quite different.

What puzzles me is the lack of American reaction against Deng’s Vietnam War. After all, it was the anti-Vietnam War generation of Americans in charge at the time. But when Deng invaded Vietnam, there was very little American resistance. Carter and Mike Oksenberg didn’t seem to care, and the anti-war China scholars didn’t protest either.

Yes, I remember that. It’s interesting. When Russia invaded Ukraine, we cared. And if China invaded Taiwan, we would definitely care. But somehow, with Vietnam, Americans were just so tired of the war that they couldn’t express outrage anymore. I’d call it the ‘Vietnam Exhaustion.’ Overall, the public opinion just didn’t care; people didn’t want to hear about Vietnam anymore. They went from thinking the war was good to terrible and couldn’t see the nuances. Cynically, since the communist government of Vietnam won the war, some might have been happy to see them get hit.

You wrote that some Americans suspended their critical lens regarding China while they were more suspicious and critical of the Soviet Union and its institutions. With China, there’s often wishful thinking and optimism.

Exactly. We tended to ignore the messy parts or complications. It’s like cheering for a football team — you get excited for one side and might switch when something happens. Americans always had an oversimplified view of China.

One of the most influential books for me was the Edgar Snow book, Red Star Over China. Snow had his romantic views of China in his own way, writing about being on the Long March and the poor communists succeeding against all odds.

Against the corrupt, capitalist, nationalist government.

There’s a wonderful book, Two Kinds of Time, written by Graham Peck during World War II that was very influential for me. It might seem dated now, but I was stunned when I started studying China. It offers a much more sophisticated take on China than Red Star Over China, written around the same time. Peck was in China for a long time and explored two different ways of looking at the country.

Opening the Times’ first Beijing Bureau in Peking Hotel in the 1980s

The first time I got to Beijing was in December 1978, shortly before Deng came to the U.S. I had a tourist visa. It was the start of the Democracy Wall movement, so someone took me to see it. I was stunned by the posters. I got in as a regular American tourist, not a correspondent, so I had to be careful. At the Democracy Wall, I started talking to people looking at the posters.

In the beginning, it wasn't easy to talk to anybody. They feared being seen talking to me, even though they might have wanted to talk. So, I always just took chances and began talking in Chinese to anyone I met. I would often get on the train, just hoping that somebody would sit down beside me to start a conversation.

I remember reading this funny scene in your book: You get onto the train, and the train waiter asks if you are a journalist. You say yes, and they put you into an empty cell. When you want lunch, they tell you to come after everyone is finished. And so when you go, you have a whole empty train carriage.

Yes, and they would warn people: this is an American, a journalist. I felt like I was radioactive. Or I had a sign that said, ‘Be careful.’

Those are nice details about how it became normal for Americans to be in China. One significant step in the normalisation process was the opening of the NYT Beijing Bureau, which you undertook. Could you tell us how that happened?

It's been almost 50 years, I don’t remember the exact government agreement. China admitted several American news organisations, and the U.S. allowed some Chinese journalists. When I got to Beijing, there were The New York Times, The Washington Post, the Associated Press, and maybe The Los Angeles Times. Then, pretty quickly, a couple of TV networks like NBC and CBS joined, but it was limited to about four or five and later expanded. The U.S. accredited the New China News Agency and others.

I had to go to the foreign ministry’s information department to get my credentials. At first, I couldn’t file stories, but we quickly started sending them.

Were you excited to finally go to China?

Yes. I had been trying to do that for years.

How did you feel when you finally arrived in Beijing and opened a new office? Where was your office?

China wasn’t yet prepared to have an influx of foreigners, including businessmen. There was a shortage of offices for us. Of course, there was a shortage of housing space for the Chinese most of all. I lived in a hotel room in the ‘Beijing Fandian’ (Peking Hotel) in my first year. The Washington Post had the same thing, but the Washington Post correspondent was married to The Los Angeles Times correspondent, so they had two hotel rooms.

That would be the Matthewses*.

Yeah, the Matthewses and their some small children. At some point, the Christian Science Monitor was allowed in. I had one hotel room on the third floor of the ‘Beijing Fandian’. That was my office, living space, and everything else. But I couldn't feel sorry for myself because most Chinese didn't have a room nearly that nice at the time.

*Linda and Jay Matthews, respectively, was China correspondents for The L.A. Times and The Washington Post at the time.

Peking Hotel was the best. What was it like?

It was comfortable and crowded. It was like an apartment because most people were actually living there, not just spending a few nights. There were a couple of restaurants downstairs.

I stayed at the Peking Hotel for several months while waiting for an office space. The Peking Hotel was an iconic place where foreign journalists and diplomats stayed, so it was a central hub for information. Eventually, we opened The New York Times Beijing Bureau in the hotel. It wasn’t luxurious, but it became our base.

It quickly became evident that the elevator operators were sent by the Ministry of Public Security. They kept track of whoever came in and out. There were probably people from the Ministry of Public Security at the front door, asking any Chinese who entered to show their credentials.

I occasionally tried to bring in a Chinese guest, but they would be stopped downstairs. It was awkward. The Chinese visitors would only enter if they were unafraid of being found out. I couldn't really meet people at my office. I had to go somewhere else. Often, it was in a park or restaurant. There was a constant “battle of wits” with the Ministry of Public Security, trying to meet people, ordinary or important, without being reported back. I felt that I was being watched in some way almost all the time.

I had a Chinese assistant, and I suspect that he was supplied by the Information Department of the Foreign Ministry. I'm sure he also reported to somebody in the Ministry of Public Security.

I came to think that he was reporting once a week. My Chinese friend said he would have to make a report on me regularly. One time, he was out for lunch, and a phone call arrived. I answered in Chinese. They asked for him, and I said he was not here. They said, “Tell him when he comes back that he doesn't have to make his report on the foreigner today.”

That happened several times, so I said, “Okay, I'll tell him.” It turned out I was being watched, as were other correspondents. Since they thought The New York Times was part of the American government, I was an especially interesting target to watch.

“It felt like living in a fishbowl - being examined all the time.”

How did you write stories back then?

I had a typewriter. Do you remember typewriters?

I've never used one, but I've seen them in museums.

At that time, I had to go to the telegraph office on the main avenue to send my stories. I'd drive there, type my copy, and hand it in. They would send it, but it allowed them to read it first.

The Chinese government got an advance copy of everything you wrote.

Exactly, it felt like living in a fishbowl - being examined all the time.

How did you work with editors in New York?

It's a 12-hour time difference, easy to remember since it’s the exact opposite. If it's 6 p.m. in Beijing and I’m done for the day, it's 6 a.m. in New York — my editors aren’t at work yet. Back then, you paid for telegrams by the word, so they always told us to keep it short to save money. We communicated through telegrams and could eventually make transpacific phone calls, but you had to reserve the call in advance. You couldn’t just pick up the phone and dial New York.

What kind of stories were you looking to report, and did the editors have ideas of what they wanted?

There are several things I targeted. I had to cover typical news stories — political events, U.S.-China relations, economic reports, and commercial agreements like Pan-American Airlines getting permission to fly to China. However, I was more interested in stories of daily life and how Chinese society worked, which is reflected in the book.

What did the editors want?

They wanted both. I pushed as much as possible to learn about daily life and how communism played into it.

Just before I got to China, I signed a contract to write a book. It was competitive as The Washington Post and The L.A. Times correspondents also had book deals. I picked stories I had written for the paper that could fit together and be expanded into book form. After all, news stories were only 600-700 words.

How did you manage writing a book while doing news articles?

I didn’t write the book in Beijing — there was no time. I wrote it after I was back in the U.S. I bought a house in Boston, set up an office in the basement, and worked from early morning to late at night. In Beijing, I was constantly chasing the beat and writing two pieces a week.

What's your drill? What's a typical day like for you?

Every day was a little different. Sometimes, I would just walk around the streets and visit restaurants or stores.

The best experiences were on trains. With few flights available, train travel was the main way to get around China. On trains, Chinese people sat next to me, and I’d start conversations. I knew they were taking a risk. Some had studied in the U.S. years ago, spoke good English, and hadn’t talked to an American in 25 or 30 years. They were happy to talk and share what had happened since the communists took over.

You once wrote a story about a woman who wanted to talk to you late at night but got pulled away by the police near the Peking Hotel. They said she wasn’t allowed to talk to foreigners at night.

Yeah, that happened. I was always happy when people talked to me, but I worried about what would happen to them. I later heard some were picked up by the police and got demotions.

“One senior person I met was Sun Yat-sen's widow, Song Qingling, who had almost a palace for her residence. She was very hospitable to me, and I met others in her family.”

Did you develop personal relationships with Chinese intellectuals or officials of the time?

With officials, it was extremely hard. Sometimes, I met the sons and daughters of high-ranking officials who wanted to know more and even travel to or study in the U.S. They would talk about life inside the party. That was a goldmine when I found someone like that. The people I talked to were the grown children in their twenties, thirties and forties.

One senior person I met was Sun Yat-sen's widow, Soong Qingling, who had almost a palace for her residence. She was very hospitable to me, and I met others in her family. I met several children of PLA generals. They were willing to talk to me, but I never met their parents. I left their names out when writing the book. Perhaps some generals learned about the United States through children who had contact with foreigners because it would have been too damaging to have contacts themselves. Later, the children would be trained in the U.S., get jobs with American companies, and make money. That hadn’t happened yet; those deals were still a few years away.

In the end, you didn’t actually live in China for too long.

I was in China for two years before returning to write my book. The Chinese government was angry with my book, so I resigned myself to the idea that I wouldn’t be able to go back. After Tiananmen in 1898, I did briefly return to write a couple of new stories and the final chapter of my book, but I couldn’t go back to cover China again.

The book wasn’t critical, just a portrait of what was going on, but the government circulated internal reports saying I was “fan hua” (anti-China) and warned people not to contact me. Interestingly, later, the Party History Department asked me for permission to translate and publish my book in Chinese.

Maybe I could go back now, and everything would be okay. Maybe they’ve forgotten about me. Writing the book felt like closing a chapter — China was one chapter, and I needed to move on.

After I met Elizabeth and moved to New York to pursue her, we married, and The New York Times found other assignments for me. One editor had the idea for me to interview a young Black man in prison for multiple murders. I wrote a story that made the front page of The New York Times again. The story eventually led to a book, which may also be made into a movie or, at least, a podcast series.

This would be All God's Children. How did you feel about that transition—leaving China and reporting on crime in Boston?

It wasn’t the conventional path.

Have you ever gone back to China?

Only in 1989. I arrived right after Tiananmen, and The New York Times sent me because of it. At first, it wasn’t clear if I could get in, but I did. I think I got in because the government was preoccupied with bigger problems.

I've become more interested in Vietnam as an ongoing issue. For the past 30 years, China has been rising, developing, and opening up. It became interesting to people but less so for me. It would be awkward to go back as a journalist. I had seen China at a certain time, and after visiting again, I was ready to move on.

It’s not that I dislike China — I still speak Chinese to people when I can — but I was drawn to other challenges. The crime story in the U.S. is ongoing, with deep connections to class, race, and regional challenges.

Trump, Interactions with other American Politicians and life after China

You met President Truman in the White House as a kid. Did you meet other American presidents later in your life?

I saw Kennedy once just after he was elected president because of my Harvard connection, but I don't know him. I met Carter because of something in the White House about China. I shook hands with him. He was the reason why Deng Xiaoping went to Atlanta on his 1979 trip.

Ronald Reagan once came to Saigon as the governor of California on a fact-finding mission. He held a news conference after spending less than two hours in the city and said, “As I choppered over Saigon today, I never saw it looking so good.” It was his first time in Saigon, and I reported that to The New York Times. Reagan seemed mentally gone even back then, ten years before his presidency.

I met George H. W. Bush when he was the liaison officer in Beijing, and we talked about China. He was a smart, patrician politician, but we didn’t have a close relationship. I met Clinton, but that’s about it.

Obama?

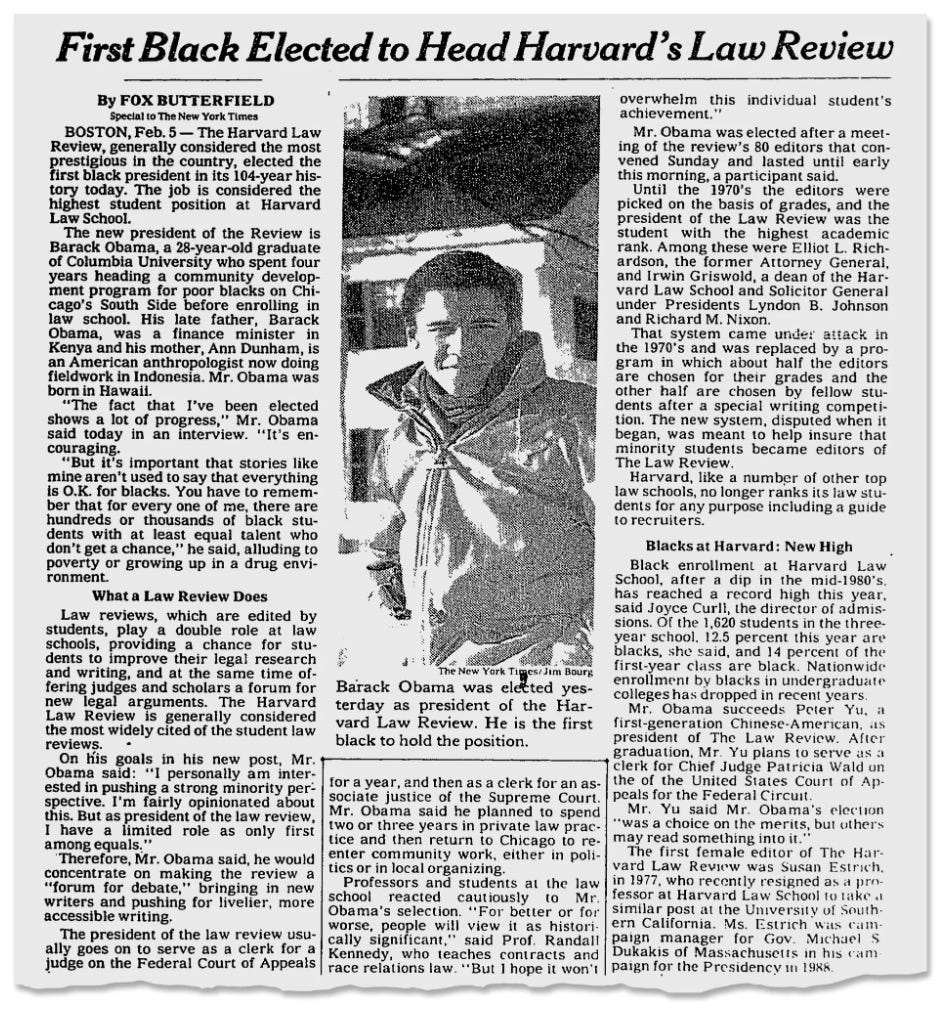

Barack Obama was the first president I really got to know. After returning from China, I asked The New York Times to work in Boston. I had been in Asia for a long time and wanted to settle down with my family, so they gave me the Boston Bureau. One day, I was in Harvard Square and saw The Harvard Crimson, which had a story about the first African American elected president of the Harvard Law Review: Barack Obama. I called my editor, explained it, and they sent me to meet him. I went to his apartment in Cambridge and wrote the story, which went on the front page of The New York Times the next day — his first time in a national publication.

Obama was smart and charming. I didn’t know he’d become president, but he had the potential. I told my wife, “I just saw the guy who will be the first Black president.” I stayed in touch with him, though not closely.

Have you ever met Trump?

I spent a lot of time with Trump.

Oh, really?

When I first met Elizabeth, I was living in Boston but she was in New York. I asked the Times to find something for me in New York. One of the first assignments for me was to meet Donald Trump, who had been a Democrat but decided to become a Republican to run for president.

This would be in the ‘80s, wouldn't it?

This was 1986 or 87, when he wanted to enter the New Hampshire presidential primary. He'd inherited his fortune and just built Trump Tower in Manhattan. He didn't know anything about American politics, but he decided his next step would be to become president and asked The New York Times for an interview. So, The New York Times assigned me to the job.

God bless you.

I wrote a story about his attempt at the presidency. He loved the story and called me up and said, “Fox, that's a great story. I want to invite you to a party. We're having the grand opening of Trump Tower. And can you come?” I asked if I could bring my girlfriend. He said sure. So Elizabeth and I attended the grand opening of Trump Tower; I had to rent a tuxedo. Then he said, ‘I'm going to go up and fly to New Hampshire. Can you fly up to New Hampshire with me?” So we flew to New Hampshire in his private jet and spent a week travelling.

Just the two of you?

Yes, basically. I remember one time we were in Portsmouth, a small city in the rural state of New Hampshire. We went into a diner, and Trump introduced himself to the people. Afterwards, Trump said to me, “Fox, isn't this amazing? All these people came out just to see me, Donald Trump.”

His ego has certainly stayed consistent since then.

That was 1987. He then invited me to his winter home in Mar-a-Lago. We spent five days with him there, which he had just acquired and was in the process of fixing up. I spent several weeks with him and wrote two stories, and he liked them both. Then, The New York Times moved me on to other things. But Trump kept calling to say, “Fox, you got to come around and see me. We've got more stories to do.”

He would periodically call every few months for several years. We had ‘guanxi’ of some kind. I liked him then, but he was ambitious and rather egotistic. Would that be a fair term? I did attend several more of his parties at Trump Tower until Elizabeth told me, “You've just got to stop talking to this guy. Tell him to stop calling.” This was way before what we are seeing now. I never could believe that he really would become president.

Recommended reading

Fox Butterfield, All God's Children. Knopf, 1995.

Fox Butterfield, China: Alive in the Bitter Sea. Times Books, 1982.

Graham Peck, Two Kinds of Time. Houghton Mifflin, 1950.

Edgar Snow, Red Star Over China. Random House, 1937.

Acknowledgement

This newsletter is edited by Caiwei Chen. The transcription and podcast editing is by Aorui Pi. I thank them for their support!

About us

Peking Hotel is a bilingual online publication that takes you down memory lane of recent history in China and narrates China’s reality through the personal tales of China experts. Through biweekly podcasts and newsletters, we present colourful first-person accounts of seasoned China experts. The project grew out of Leo’s research at Hoover Institution, where he collects oral histories of prominent China watchers in the West.

Lastly…

We also have a Chinese-language Substack. If you are on Instagram, follow us @peking.hotel. Speaking to these thoughtful individuals and sharing their stories with you has been a privilege. Their stories often remind me of what China used to be and what it is capable of becoming. I hope to publish more conversations like this one, so stay tuned!

Share this post